Atlanta BeltLine Embraces Graffiti Artists Amid Changing Urban Landscape

As graffiti morphs from real estate blight to urban amenity, Atlanta’s style writers are driving forces in a conversation about public art.

By Brentin Mock

bloomberg.com (Link to original)

Jun 01, 2024 01:15

The graffiti-slathered Krog Street Tunnel exists at a collision between old and new Atlanta. On one end, its entrance sits blocks away from the Sweet Auburn district, birthplace of civil rights legend Martin Luther King, Jr. and the site of his tomb. On the other end are Cabbagetown, once home to mill workers, and Reynoldstown, founded by formerly enslaved African Americans, both of which have undergone dramatic neighborhood change.

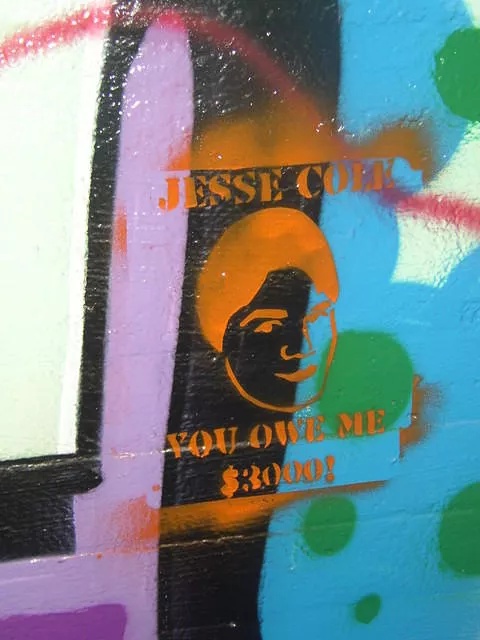

Markings from the various stages of the area’s transformation are etched, scribbled, Sharpied, bubbled, tagged and spray-painted all through the underpass and both tunnel entrances, in layers upon layers of unadulterated graffiti, with timestamps reaching back decades. The overarching narrative is survival.

Krog Street is one of several safe spaces in Atlanta where graffiti artists — and really anyone with a spray can — can get busy on the walls, unencumbered. Residents have not only conceded the tunnel but have since supplied additional walls for public graffiti creation and consumption.

It’s indicative of the city-at-large’s unofficial tolerance of the practice. There are few stretches of Atlanta where you won’t find elaborate graffiti pieces and burners draped across walls. Such activity was once a priority law enforcement target, under the controversial auspices of “broken windows” policing. But today, while graffiti remains illegal in most of Atlanta, priorities have shifted. As in many cities around the world, graffiti has become part of the urban fabric – once seen as a real estate blight, but now commonly viewed as an asset.

In Atlanta, graffiti artists have worked for years behind the scenes to ensure their culture’s preservation and decriminalization.

“This culture needs to be on the record,” says Antar “Cole” Fierce, who’s been archiving Atlanta’s and New York City’s graffiti scene since the 1980s. “And people need to see that the earliest people to do this were Black kids and Latino kids. Because 100 years from now this story could get switched around, especially now that people are starting to embrace it.”

Graffiti has been around as long as humans have held marking instruments. In the US, it was seen as early as the Civil War, when Union and Confederate soldiers left behind graffiti at various sites — George Mason University is developing a digital archive of this in North Virginia. It has always existed to tell the story of who lived in a certain place, at a certain time, under certain circumstances.

However, since at least the mid-20th century, city leaders and traditional arts organizations have viewed graffiti through a criminal lens, often affiliating it with gang activity. While that might ring true in some places and contexts, graffiti is more normally practiced by street artists with no such affiliations. In fact, it’s considered a foundational element of Hip Hop that effectively brought about a gang truce in the Bronx in the 1970s.

That truce didn’t stop New York City’s 1980s-Mayor Ed Koch from escalating the war on graffiti that his predecessors started in the 1970s. The crackdown led to mass incarceration, police brutality and even deaths. But those crusades also didn’t stop graffiti from spreading to cities like Atlanta, now considered a style-writing mecca of the South.

Earlier this year, filmmaker Will Feagins released the documentary City of Kings, which features Fierce and several native artists showing and telling the history of Atlanta’s graffiti scene. It was recently accepted to the Hip Hop Cinefest festival in Rome. The film showcases the more “personal side,” says Feagins, of the people behind the wild, street-calligraphy spray-painted across urban walls.

“Their creative passion happens to be frowned upon by a lot of people but it doesn’t necessarily make them bad people,” says Feagins. “As I saw the connection between graffiti and public art, I wanted to also help the audience see how they are linked.”

The culture has made breakthroughs in several cities, such as Miami, where the Wynwood Walls and Museum of Graffiti arguably launched the modern movement of city-embraced graffiti, and Philadelphia, where graffiti culture as we know it today began in the late 1960s.

To secure graffiti’s place in Atlanta, Fierce enlisted help from an entity that many once thought might help spur the culture’s demise: The Atlanta BeltLine, a 22-mile ring of former railroad tracks that are being converted into walking and biking trails around the city. While the BeltLine is providing much-needed alternative modes of transit and leisure in the heavily car-dependent city, it has also raised concerns about the acceleration of housing unaffordability, and the erasure of Black landmarks.

But the BeltLine has actually become a lifeline for graffiti culture, helping to keep areas like the Krog Street Tunnel secure for style writers to continue their art.

“Style writing on the BeltLine is here to stay, even in the future development of the trail,” said a spokesperson for Atlanta BeltLine Inc. in a written statement to CityLab. “When the 22-mile loop is completed in 2030, our goal as an organization is to ensure the work of style writers who proceeded this project and those who have contributed to it since we began will remain, showcasing the legacy, creativity and culture of Atlanta.”

While Krog Street is open to the public to tag, other protected graffiti sites along the BeltLine are not. One particular area, the “So So Def Walls,” is considered so sacrosanct and off limits to civilian hands, that even most style writers need a special invitation to work there. That invitation could only come from original style writers such as “SAVE,” the site’s founder, and Reveal “Poest” White, today its official custodian and guardian.

The “So So Def Walls,” named for the once-famous nearby billboard advertising the legendary So So Def Records label, were once inaccessible to pedestrians. Writers had to brave through an Atlanta police property detention compound and then through a thicket of weeds, poison ivy, and brush to get to the walls, which sit below the 75/85 highway.

However, since the BeltLine cleared a path through the site, where civilians now jog and bike regularly, it’s become subject to random spam and scrawlings that even graffiti artists consider vandalism. The walls are adorned with style pieces dating back to the ’90s, from artists invited both locally and from as far away as California, and even other countries.

White says lately he’s spent considerable time cleaning up unsolicited taggings, namely anti-“Cop City” messaging opposing the city’s incoming public training center complex. While anti-“Cop City” and “Defend the Forest” messages have sprung up throughout the city, White says they’ve been tagging on top of pieces in areas protected for seasoned graffiti vets.

“I literally had to go to their team and tell them, ‘Please, don’t do that,’” says White. “You can’t say this is about a voice, and then you try to silence someone else’s voice so that your voice can be heard. It doesn’t work like that.”

Preserving these walls was an endeavor that White and Fierce had taken up long before the BeltLine came along. Convincing BeltLine authorities of the area’s right to exist meant enlisting the BeltLine’s then-art director Miranda Kyle, who became a formidable ally. As a public arts activist with a focus on “cultural place-keeping versus place-making,” Kyle saw the style writers’ plight as part of her larger mission to challenge policies around who gets to decide what is legitimate art and what can occupy public space.

“The reason that space is so sacred is because, from a city historical lens, the redlining, and the breaking up and destruction of so many neighborhoods when the [75/85] highway came through,” says Kyle. “I saw the So So Def Walls as a reclamation of space and identity, and an exclamation of, ‘We will not be erased,’ that really resonated with my politics.”

White took the rare, if not forbidden, step of publicly disclosing his government name to become the face of this protectionist front — a risky endeavor given most writers keep their identity cloaked to guard themselves from police. Separately, the Atlanta Style Writers Association was formed, in part to provide cover for artists who also wished to remain anonymous while advocating for their work.

Their collective efforts resulted in a fruitful partnership between writers and the BeltLine, where several areas along the trail have either been preserved or created for writers to continue their traditions. A map of some of these locations is available on the Atlanta Style Writers Association website. The BeltLine now funds White to maintain the site and conduct programming there.

“This means too much to Atlanta for me to let it fall by the wayside,” says White. “So we went to board meetings, and spoke up to make sure that other writers, and up-and-coming writers, had a place that solidified that they had a right to be there.”

One name found on the So So Def Walls these days is Sparky Z, a native Atlanta writer who started in the 1980s, when crews like the United Kings and the Five Kings ruled the day. Back then, Sparky Z couldn’t envision his art form would ever be embraced, nor did he want it to be — style writers don’t seek the blessings of the law.

However, as Atlanta began to crank up law enforcement in the 1990s in the lead-up to the 1996 Summer Olympics, he began seeing many of his friends arrested and jailed.

Around 1993, he gave graffiti up, turning to music production while working at a car rims shop alongside another young artist named Amy Sherald, a Spelman University student who today is perhaps best known for her portrait of First Lady Michelle Obama.

As he faded from the scene, he watched the city paint over walls that he and his peers tagged and sprayed up for years. He regrets not taking pictures of his work back then, when carrying pictures of your work was incriminating evidence.

Fortunately, Fierce was documenting the scene, having stayed in Atlanta after graduating from Clark Atlanta University in 1995 with a degree in history. Years later, he obtained a master’s in creative education from Georgia State University, which he used to transition from writing on trains and buildings to teaching about style writing.

He’s the co-producer and primary narrator of Feagins’s City of Kings documentary, which also features Sparky Z, a fabled artist at the time given his early ’90s exit. But Fierce was able to bring him out the woodwork for the doc and even inspired him, at 54 years old, to start writing again.

“I’m back on the graffiti scene because of those guys,” says Sparky Z. “They said they had been looking for me for 30 years.”

To be clear, graffiti is illegal in Atlanta, a violation of the city’s nuisance ordinance. However, enforcement relies upon police catching them in the act or residents reporting it to police. Lately that hasn’t happened, given that many communities are now in on the act. Atlanta police, who at one point prioritized cracking down on graffiti, now accept that it is sanctioned in some parts of the city.

Atlanta Public Affairs Officer Aaron Fix acknowledged to Citylab that “there are specific free areas within Atlanta where public art has been accepted by the community, such as the Krog Street [Tunnel].”

Police at MARTA, Atlanta’s transit network, seem similarly generous with enforcement. They’ve made just three arrests over the last five years, all of them in 2023. Yet the train yards and stations remain fortified with cameras and officers who patrol the areas to ensure there are no trespassers.

The more lenient attitudes in Atlanta, and cities beyond, could be tied to the fact that graffiti’s value has significantly increased from the days when it was just seen as vandalism. On April 15, many mourned the death of Patti Astor, a queen of 1980s Manhattan nightlife who introduced street-based artists such as Jean Michel-Basquiat and Keith Haring to the exclusive art districts of Manhattan.

While that marriage didn’t necessarily translate to other cities, today graffiti is omnipresent in many of the hottest real estate markets. In trendy Atlanta neighborhoods like the West End, Midtown and Krog District, the volume of marked-up breweries, cafes and boutiques seems to track with the marking-up of home prices around them.

It’s not just graffiti. Community appetites for murals in general have widened over the past few decades, as a way to enliven buildings both new and old. The Living Walls series, responsible for a proliferation of murals across Atlanta, is a popular example of how the city has captured this zeitgeist. Larger-than-life depictions of icons from civil rights veteran and former congress member John Lewis to Hip Hop legends Outkast are Instagram favorites worldwide.

Many Atlanta muralists are former and even current style writers who credit graffiti for today’s acceptance of wall art. Graffiti artists also taught some of today’s muralists how to transition from the canvas to the walls: what paints to use, how to control paint from dripping outside the lines, and the best ways to guard their work from the weather. Former BeltLine art director Kyle says this is evidence that despite graffiti’s past devaluation and criminalization, it has been foundational to the modern public arts movement.

“We set out to prove that style writing is just as important and profound as street murals are to our cultural landscape,” says Kyle. “They're not lesser versions of art. They are an important part of our public space and cultural dialogue — the forebearer to public art in the city, I mean, honestly, the forebearer to public art across the country.”

There is, of course, a tension between some traditional style writers and those who’ve gone legit, with the former rejecting permission and profit. For decades, graffiti artists dodged police while accomplishing death-defying feats like scaling high-rises, bridges, billboards and roadway signs, with their names spotlighted in the near-heavens as their only form of compensation.

Some veterans feel that those who’ve paid their dues now deserve the right to indulge in the spoils of the public arts industry.

“It’s kind of a love-hate relationship for me,” says Sparky Z. “But at the same time, I want to become a muralist. I love the fact that it’s accepted by everybody today. So, I’m not complaining, because that’s an opportunity for us to go pro, you know?”