A battle over this Inner Richmond wall speaks to a very San Francisco crisis

Column: The Green Street Fund's Luke Spray on the tyranny of the gray wall

Luke Spray

May 9, 2025, for SFGate

There’s a battle underway on Clement Street. The battlefield is a plywood wall between 9th and 10th avenues, and it’s attracted a wide array of challengers. Local artists, party promoters and wheatpaste advertisers. Teenage taggers, protesters and walking club enthusiasts. Each takes their shot. But the victor here is always the same: another thick slathering of gray paint.

It’s a gray that’s more relentless than the afternoon fog. A gallery-sized version of photographer Michael Jang’s famous shot of the Golden Gate Bridge’s 50th anniversary was gone so fast I didn’t even get a picture of it — though, amusingly, a small print of it was glued to a wall nearby a few days later. Typical Jang. In between the bouts of gray, the space quickly reverts back to a delightful hodgepodge, a mix of protest statements, comedy night flyers and Converse ads. By contrast, each fresh slathering of gray is monotonous, only seeming to draw attention to what a dead zone the wall creates on an otherwise vibrant section of Clement. Yet this battle isn’t just graffiti vs. the gray; it’s part of a longstanding tussle over San Francisco’s streets that goes back to the 1800s and continues to confound us.

Vibrancy — or, more specifically, the lack of it — is all the talk these days. “What is the city doing to cure our dreary downtown?” we ask. Yet the gray wall in the Inner Richmond prompts questions about a party that’s largely escaped criticism in this discussion: absentee property owners and the spaces they neglect. Street art often serves as an indicator of these deserted properties, revealing the strange dynamics of a city more focused on combating graffiti than the blighted properties that serve as their canvas.

There’s a fundamental piece of urban psychology that the gray wall acts as a counterpoint to. It’s a rule you intuitively know and understand. It says that great places have something new and interesting to see every 15 to 20 feet. The foremost researcher on this subject, Danish architect Jan Gehl, describes this as “3 mph architecture.” He points out that there’s a reason why so many of our pre-car commercial corridors maintain this architectural rhythm: it’s a pedestrian’s pace, priming us for sensory delights every few steps.

Clement Street could be Exhibit A for what we’ll call Gehl’s Law of great streets. It’s made up of small, deep storefronts, creating plenty of opportunities to engage with local businesses and each other. It’s a sociable streetscape. Each storefront can be covered in about four or five seconds of walking, which corresponds with the natural pace for processing our surroundings. Gehl’s Law also explains why many parts of SoMa and the Financial District feel so uninviting. They’re repetitive and unexciting, places starved of pedestrian stimulation in a city that’s otherwise a visual feast. No wonder we’re trying to drink our way out of the problem.

If San Francisco is a feast for the eyes, street art may be the amuse-bouche. You’ll find it occupying otherwise unremarkable stretches of a street, or tucked away, waiting for you to discover someone’s artistic enhancement, a small treat offered up to the urban environment.

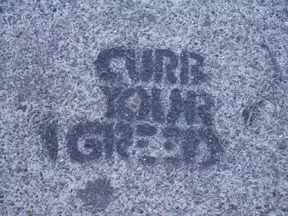

There’s a broad range of what might constitute street art. On one end of the spectrum, you’ve got sloppy tags and Sharpie scribbles. Do those count? On the other end, works from artists like Jang, Agana and Megan Wilson bleed from the canvas onto our culture. Those definitely count. Somewhere in the middle you’ll find sidewalk stencils, cryptic flyers stapled to telephone poles, and the “listen 2 the happys” guerrilla marketing campaign.

“It’s like a tree,” says Agana, a local artist whose own work spans the spectrum from graffiti to fine art. “The art in the streets has branched off into so many genres. Stencils, wheatpaste, lettering, characters, it’s all just public art.” You can debate the merits of any particular piece, but each adds a bit of visual stimulation, a reminder that the city is alive and sensitive to an individual’s influence upon it.

Back at the gray wall, I look up the address and find a for-sale listing. A rendering of the space as a glassy restaurant sits below the sales price, $2.9 million. The restaurant rendering obscures the fact that this building is a prime candidate to become housing under the city’s proposed family zoning plan, a fact that’s revealed in the building’s price tag. It’s priced to build. Housing would be a welcome addition here, as everyone should be so lucky as to live in the Inner Richmond, but I fear the possibility of housing promises an extended lifespan for the gray wall. It’s good business for an owner to bide their time until their building fetches some inflated price, but it makes for bad neighbors. Yet speculative landowners don’t seem to mind. For them, this is just a waiting game — and it’s an old game at that.

The question of what to do about land speculation has long vexed San Francisco. In 1879, a young journalist living on Rincon Hill, Henry George, wrote a popular book that described how land speculators reap value they don’t earn, benefiting from the improvements made by their neighbors while their lots lie dormant. It can be summarized by a phrase later turned into a billboard: “Everybody works but the vacant lot.” To remedy this, George advocated for a new system, a “land value tax” that taxed property but not the structures or improvements made upon it. In theory, this change would prompt owners to make the most of their properties, eliminating land speculation while reducing economic inequality. This, in a nutshell, is Georgism. It’s a cult favorite economic theory if there ever was one, born right in our backyard from problems we still deal with today.

One way San Francisco is trying to address this issue is through the city’s commercial vacancy tax. It charges property owners for each linear foot of vacant business frontage. The building with the gray wall was not listed when I looked through the program’s database. It seemed like a strange omission, as the space has been vacant for years now. Perhaps I was missing something, so I dug deeper. I was unsurprised to find a number of calls for graffiti removal when I looked at 311 requests. Yet there was a curious note at the bottom of one of them: “Property has been scheduled for abatement with opt-in crew.”

The opt-in crew, I came to learn, is a team from Public Works. They’re part of a pilot program for “courtesy graffiti abatement.” Which sounds lovely when you imagine it benefiting mom-and-pop shops hit by random taggers, but when it supports speculative landlords who’ve otherwise washed their hands of their properties, it becomes a bit more sinister. You and I have been paying to paint over Jang murals, a courtesy we provide to those who will profit from neglecting our neighborhood villages.

How this property escaped from the vacancy tax yet benefits from a $2 million taxpayer-supported graffiti removal program feels like a uniquely San Francisco problem. We’ve got multiple vacancy tracking programs, all of which fail to track the absurdity of the situation. We’re footing the bill to clean up graffiti while giving a free pass to those who create the canvases. It’s a bizarre bureaucratic ouroboros that devours our already limited budget while diminishing civic capacity.

When you see a building sit vacant for years, or read a story about SF’s “most hated landlord,” it’s easy to wonder about how some clever Georgist tax policy might fix it. But the lackluster rollout of the vacant storefront tax doesn’t inspire much confidence. When you compare it with our zealous approach to street art removal, it seems to imply that we’ve shifted our focus toward the issues right in front of us, rather than their underlying causes. Courtesy graffiti abatement becomes a symbol of a city that’s functional, a distraction from our inability to resolve the vacancies at the root of our vibrancy crisis.

“Graffiti is freedom of speech, it’s a reflection of society,” Agana told me. “More than vandalism, it’s about combating consumer culture.”

In this light, the wall on Clement seems to be a collective shout, as contributors to the city speak out against the forces that seek to consume it. Agana pointed me toward Oceanwide Plaza in Los Angeles, a 40-story abandoned eyesore that the city preferred to overlook until graffiti made its presence too hard to ignore. San Francisco has its own Oceanwide development debacle. It’s one part money pit, one part object lesson on how negligent property owners swallow parts of the city where we might otherwise find vibrancy. The plywood wall around that void seems to suggest that the only response is another coat of gray paint.

“Who do you think are the real vandals in this situation?” Agana asks. Neglect reappears as a canvas, just waiting for inspiration to strike.